Making Mayonnaise from Scratch Is Easy and Delicious

Mayonnaise is the Rodney Dangerfield of great sauces. It gets no respect.

Although credit for its origination is not without controversy, the most likely account is that mayonnaise was invented by a chef to the third Duke of Richelieu (the first Duke of Richelieu being best known as the villain in The Three Musketeers). In 1756 the Duke successfully laid siege to Port Mahon on the isle of Minorca, 140 miles Southeast of Barcelona. Once the British surrendered and decamped for their home turf, the French chef intended the Duke’s victory feast to include a traditional egg-and-cream sauce, only to discovery that the garrison larders didn’t have any cream. So he substituted oil, creating a sauce named mahonnaise after Port Mahon.

That historic accident foreshadowed the diminutive treatment mayonnaise would later receive. Anything taking its name from the port city to an island whose moniker literally means “minor” is inviting disrespect.

Escoffier tried to elevate the sauce to the glory it deserves. In his 1903 Le Guide Culinaire he listed mayonnaise as one of the five great sauces of French cuisine – known as the five Mother Sauces. But nowadays mayonnaise is routinely denied that lofty status, in no small part because the English translators of Escoffier’s epic cookbook (perhaps still smarting over their country’s defeat to the French at Port Mahon) dropped mayonnaise from translated editions of the book’s great sauce list. In its place they elevated hollandaise sauce, a distant cousin to mayo that’s made with melted butter instead of oil. I’m sure it’s entirely a coincidence that both the name and origination of hollandaise sauce derive from Holland, not France.

Nowadays mayonnaise isn’t considered a sauce at all. It’s been demoted to condiment status, alongside (both categorically and often physically) ketchup and mustard. All three are popular, common, almost exclusively produced by the corporate food industry, and generally ignored in fine dining.

In the case of mayo, that’s a shame. For all the talk of oil and water never mixing, mayonnaise is the perfect embodiment of that very phenomenon. Its creation might not rise to the same miracle status as converting water into wine, but it’s miraculous nonetheless. And while the ultimate mayonnaise delivery vehicle is probably the humble artichoke, thistles are considerably more attractive to photograph than is a mound of mayonnaise, so artichokes are the centerpiece for today’s images.

Mayonnaise is an emulsion, with microscopically small droplets of oil (each one as small as one ten-thousandth of an inch across) suspended in a water-based, acidic liquid: Typically vinegar or lemon juice. The agency causing water molecules to embrace and hold oil droplets in place is lecithin. Egg yolks are packed with lecithin: A typical yolk weighs about 16 grams, and one gram of that is lecithin. That’s why egg yolks are the emulsifier in almost all mayonnaise that’s eaten today. Indeed, to be labeled as mayonnaise in the United States, eggs are legally required to be included as an ingredient.

The mechanics of emulsifying mayonnaise are pretty straightforward. The water-based ingredients (the acidic liquid, egg, and any water being used) are combined in a bowl. A little bit of oil is added and mechanical energy (a whisk or a motor-driven blade of some sort) breaks the initial oil droplets into smaller and smaller bits. The water base coats the oil droplets, and the emulsifier binds the oil particles to their water coating just enough to keep the oil from coalescing back together.

As more oil is added and broken into further small droplets the existing droplets, being suspended in the water base, make the emulsion thicker, which makes oil additions easier to break into smaller droplets, which allows the cook to add the remaining oil much faster than was done at the start.

That basic process can be executed in any of three ways: With a whisk, with a traditional blender, or with a stick blender. Using a whisk takes by far the longest, and is the least efficient because no amount of whisking can break the oil down into droplets as fine as can be achieved using a machine. But the result is nonetheless a silky, creamy sauce.

By contrast, outside of industrial-grade machinery, a stand blender is the most efficient piece of equipment for making mayonnaise. Its sharp blades and powerful motor cut the oil into tiny droplets much more readily than a handheld whisk can. As the emulsion thickens, the blender has enough power to continue processing the remaining oil as it’s added.

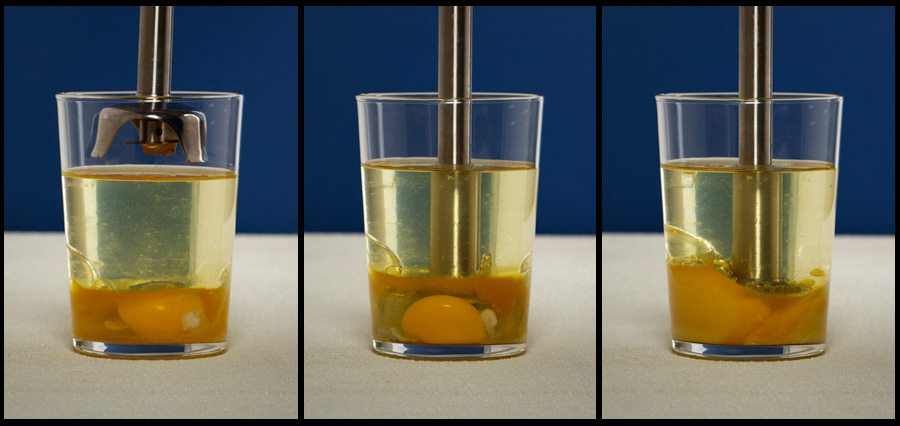

A stick blender isn’t as powerful as the stand variety, but the bell-shaped guard over the hand blender’s blades makes it a uniquely amazing tool for creating mayonnaise. Cooking guru Kenji López-Alt discovered the hand blender method a few years back. The only trick is to use a cup or glass that’s large enough for the base of the hand blender to rest on the bottom of the glass. The water-based ingredients get dumped into the glass and the oil is poured in all at once, where it floats atop the water-based liquids. All that’s needed is for the water-based ingredients to fill enough of the glass to reach the blender’s blades, like this:

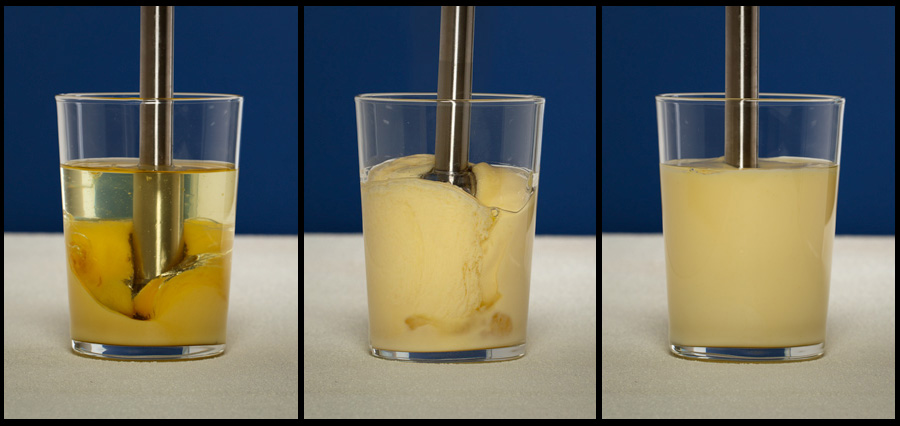

With everything in the glass, you just turn on the stick blender and the ingredients immediately blend into mayonnaise. After just a second or two you raise the blender until the blades nearly reach the surface, processing any uncombined oil near the top, then plunge the blender back down to the bottom of the glass to finish the emulsion.

The entire process takes just three seconds, compared to about 15 seconds in a stand blender or several minutes whisking manually. The result isn’t quite the equal of what a stand blender achieves, but if you want to feel like Merlin in the kitchen and have a stick blender on hand, give this method a whirl.

As for ingredients, the only essentials are oil, an egg, and something acidic (lemon juice or white vinegar being the popular choices). Salt isn’t essential, but makes the result more flavorful. Mustard also isn’t essential, and commercial mayo producers in some countries (Canada) intentionally omit it because that’s what their consumers have become familiar with. But in the United States, mustard is the background flavor that makes mayo taste like mayo.

For the basic recipe below I also include a little xanthan as an optional ingredient. Xanthan is a flavorless, natural ingredient made from fermented sugars. It’s commonly added in commercial foods because it thickens liquids and stabilizes emulsions. For home cooks it’s a fantastic additive because unlike most hydrocolloids, xanthan does its work without needing to be heated. It’s a particularly spectacular addition when making mayonnaise because it creates thicker and more stable emulsions without any extra effort by the cook.

As delicious as basic homemade mayonnaise is, that’s not really why you ought to make it. The store bought stuff is equally cheap and nearly as tasty. The real reasons to make mayonnaise from scratch are that it’s easy, it’s fast, and most important, the basic recipe serves as the base for flavored variations that can’t be bought in any store, at any price. And that’s the subject for next week’s post.

Basic Mayonnaise Recipe

Makes 1 1/4 cups

1 T (15 g) lemon juice or 2 t (10 g) white vinegar

1 egg (50 g)

2 t (10 g) Dijon mustard

1-2 T (15-30 g) water

0.4 g xanthan (optional)

1/8 t (0.8 g) salt

1 c (240 g) neutral oil (like Canola, safflower, or vegetable oil)

In the bowl of a stand blender put the lemon juice (or white vinegar), the egg, and the mustard. If they don’t come up far enough in the bowl to reach the blender blades, add enough water (typically just a tablespoon or two) until they do.

Combine the salt and xanthan (if using it) together. (Stirring the salt into the xanthan ahead of incorporating them both into a liquid is an easy way to protect against the xanthan clumping.) With the blender running at low speed, sprinkle the salt/xanthan mixture into the liquid.

Turn the blender up to medium speed. Starting very slowly (about a teaspoon of oil at a time) add the oil and let the blender process it into the water-based ingredients, which it will do almost instantly. Continue adding oil slowly at first, then after a few seconds add it more rapidly. The entire addition should take at least 10 seconds, but doesn’t need to be drawn out much beyond that so long as the initial oil is added in small quantities.

If the mayonnaise becomes thicker than you want it before all the oil is incorporated, add a teaspoonful of water, which will loosen the mixture.

Like this Recipe? Leave a Comment.

Your email address will not be published.