Recipe Measurements and Their Abbreviations

In an office somewhere in New York or Chicago or one of the other publishing hubs of North America sits the foremost authority on abbreviating recipe measurements. At least, that’s what I imagine. Publishers employ immensely literate people who focus not just on nuances like the proper usage of “whom,” but on true arcana that a mortal reader wouldn’t recognize if it was circled in red: Stuff like the difference between an en dash and an em dash, or whether two spaces must follow a period or just one.

Some such person must be the definitive authority on recipe abbreviations. But whoever it is doesn’t have a lot of influence, because the cookbooks and cooking sites I read adopt conventions all over the map.

Anyone publishing recipes on the interwebs (me, for example) faces two problems on this score. The first is that different cooks use at least two, and sometimes three completely different measures for the same ingredient. Most home cooks measure by volume: Tablespoons, cups, quarts, and the like. But a lot of cooks measure more often by weight. And everyone wants their recipes expressed in the measures they prefer.

Whether by weight or volume, the second problem is whether a given cook embraces the convenience of measuring in metric. A topic for another day is how screwy our non-metric prevailing measures are. Our teaspoons have nothing to do with tea, nor our tablespoons with tables, nor are they portioned in any sensible relationship to one another. The entire teaspoon/tablespoon/pint/gallon system is such an oddity we don’t even have a conventional name for it.  Despite how persistently we cooks cling to it, does anyone claim loyalty to “the unofficial Apothecary system of measures”?

Despite how persistently we cooks cling to it, does anyone claim loyalty to “the unofficial Apothecary system of measures”?

The good folks who published Modernist Cuisine addressed that whole problem by ignoring it. Their recipes are exclusively in metric measure. But for most people in the States, adopting the metric system is like moving to the Pacific Northwest: An incontestably excellent idea, but surpassingly unlikely to happen.

Metric/non-metric and volume/weight measures

On this blog, choosing between metric and Americanized measures is easy. Lots of cooks use each kind, so I usually give both. Somewhat less easy is whether to express measures in weight or volume. The logical measure usually depends on the ingredient, but the logical choice is not always what people want. Flour, for example, is more accurately measured by weight than by volume, but measuring cups aren’t horribly worse and are a much more familiar measure for home cooks. So with flour and other dry ingredients I typically give both weight and volume measures. Liquid measures are likewise generally expressed in both volume (U.S. standard measures like cups) and weight (typically in grams).

Salt is a special case. Recipes usually call for it in small quantities: Part of a teaspoon up to a tablespoon or so. But giving spoon measurements for salt that will be the same from one kitchen to the next is impossible because table salt, kosher salts, and flake salts all have dramatically different densities. Even among kosher salts, sodium densities vary widely, and that problem is worse among different finishing salts. By contrast, a level teaspoon of table salt delivers the same amount of sodium in any kitchen, whether the salt comes from Morton or somewhere else. So my recipes express salt both by volume (in teaspoon/tablespoon scale) and by weight (in grams), and the volume measure is always for table salt, not flake salt. You can convert by increasing the spoon measurement in whatever proportion is right for your kosher or finishing salt, or just weigh out your salt to the indicated grams and don’t fret over what the right volume measure would be for whatever salt you like to use.

Pinches and dashes

Once upon a time, someone figured it would be a good idea to establish volume measures bridging the gap between nothing and a quarter teaspoon. That must have been where ‘pinch’ and ‘dash’ came from, along with the notion that a dash ought to equal two pinches.

Thankfully that idea never really caught on, since it would be extra mental overhead in a world where too many people are stumped over how many teaspoons are in a tablespoon. So at Have Pan, there’s no such thing as a dash. On the rare occasion that a pinch steps onto the stage we’ll be talking about salt, and it will mean what you’d expect: What you get by pinching thumb and forefinger together in a small dish of the stuff. That’s roughly 0.2-0.3 g, whether you’re pinching kosher, sea salt or table salt.

Boycotting ‘dash’ and avoiding ‘pinch’ doesn’t mean Have Pan snubs small measures. They’re indispensable to many recipes. Quantities for hydrocolloids, for example, tend not only to be tiny but also are so sensitive to exact measure that they’re designated in tenths of a gram.

Have Pan recipe abbreviations

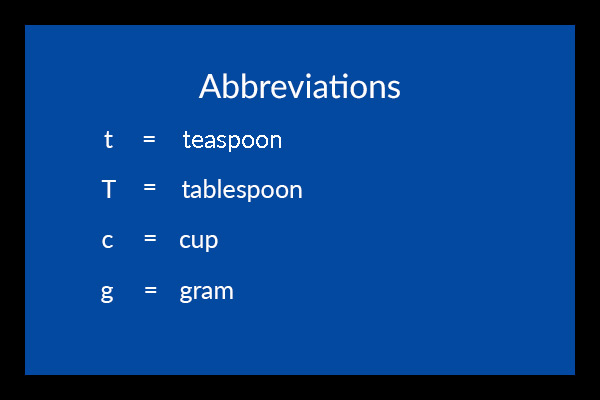

Lastly comes the delicate problem of abbreviations. Coffee table cookbooks like Alinea and The French Laundry Cookbook tend not to use them at all. But that sort of formality strikes me as silly for a cooking blog, so I abbreviate. Metric measures have standard abbreviations, so they’re not an issue. Americanized volume abbreviations, though, come in more varieties than Frango mints. Tablespoon, for example, can be “tblspn,” “tblsp,” “tbsp,” “tbs,” or “tb,” each of which can be capitalized (or not), and all of which could present with or without a period.

Because a recipe is just a tool, I use the simplest abbreviations that get the job done:

teaspoon = t

tablespoon = T

cup = c

quart = qt

gallon = gigantic boatload [I need this one approximately never]

Using just “t” and “T” has always seemed preferable to their longer abbreviations. I never mistake one for the other, but have more than once misread recipes with “tbsp” or “tspn”.

Pints are great in a pub, but not much use in a recipe. “2 c” serves just fine.

Celsius is always C, and F is for Fahrenheit. No periods. Both are capitalized because both derive from proper names and because, well, they just are.

I reserve the right to be fickle when it comes to the ounce. Fluid ounces are an endangered species here. They invite confusion and my recipes rarely use “1 16-oz bottle of goop.” U.S. weight ounces are “oz,” though for some reason I’m often tempted to slip in a period as well. If I’m expressing a pound and a quarter it might be “20 oz” or it might be “1 lb, 4 oz.” The former is easier to scale up or down, but the latter is how most digital scales would show it. If you want whichever I don’t use, you’re on your own for the mental conversion. That’s what you get for not using Teh Metric.